With Ursula K. Le Guin challenging the gender binary as early as the 1960s, speculative fiction has been pushing society’s boundaries in a way no other genre has been free to do so.

Illustration by Bo Moore

The sci-fi and fantasy television shows Torchwood, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Xena all displayed steamy same-sex, on-screen kisses well before other genres (or society) were even accepting the existence of queer culture. The genre of Speculative Fiction (SF) managed to accomplish this as early as the 1960s, both written and on screen, so casually challenging society’s heteronormative constructs at a time in history when only a handful of countries had even recognised same-sex marriage.

When the media represents non-heterosexual sexualities, we see TV shows and films littered with stereotypes. The introduction of a non-heterosexual, or queer character often requires an explicit announcement of their sexuality, defining the characters in a way that their heterosexual counterparts never are. Even more often, queer characters are the main protagonist in a tragic tale based solely on the hardships they face due to their sexuality, almost so that the personality of the individual is obscured.

In general, queer sexualities are under-represented in every genre, but we see some fantastic representation in early works of SF. SF has a unique upper hand when it comes to presenting ideas outside of the ordinary. As a genre, it is characterised by re-imagining the world to depict characters, societies and environments with a peculiar twist. In order to be immersed in SF the audience must suspended disbelief, and buy into the ideologies of the re-imagined world. The genre is able to break down the walls of oppression the same way it is able to portray a time traveling, immortal doctor who can regenerate into new forms (and genders), without the audience blinking an eye.

Doctor Who, Series 8, Episode 11: One of the show's long-standing arch-villains, The Master, 'regenerates' into another gender, and now goes by The Mistress.

Science-fiction critic Darko Suvin calls this “cognitive estrangement”, a phenomenon which applies specifically to the worlds of SF. By creating alternative realities that contradict the current norm, SF forces the audience to absorb and reflect on scenarios outside the realm of their own belief structures. In essence, a little homoerotic on-screen kiss seems a whole lot less extraordinary to conservative audiences when they can believe there are time travellers and vampires traipsing around.

On a larger scale, SF (especially literary SF) has had huge cultural impact. The novel Brave New World by Aldous Huxley was recognised as such a threat to society’s status quo that it was banned in some countries and classrooms for inspiring anti-family and anti-religious ideas. It’s not an embellishment to say that SF is the most powerful genre when it comes to stretching the imagination and challenging an audience’s ideals. It’s no wonder SF has allowed sexuality to be portrayed in vividly imagined and unique ways. Authors can create societies with entirely new genders, and film and television writers have been able to casually portray a host of sexualities without painting the character as a sexual deviant.

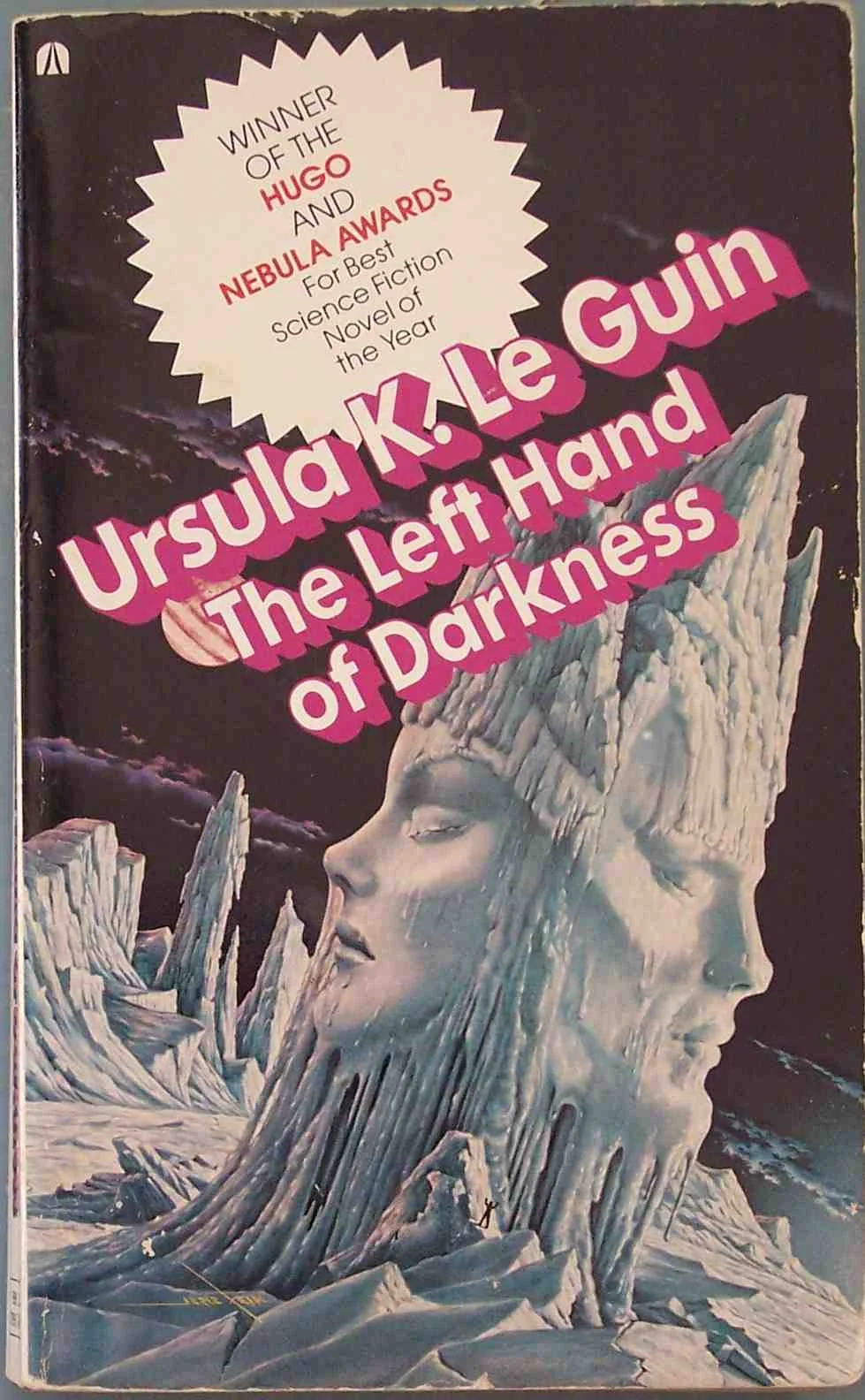

Ursula K. Le Guin imagined a world where the gender binary did not exist — a true pioneer for normalising queer culture in the 1960s. Chris Drumm/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

One such novel is The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin (1969). She creates a world in which the characters have no gender, and therefore no sexuality. The author briefly explains how procreation is facilitated by characters “negotiating” their gender during fertile cycles, but the concept never enters the actual storyline. This allows the story to centre around the friendship between the two main characters. It is unique in that it lacks all sexual politics, which inevitably occur between characters of opposing genders. With the removal of references to gender, so follows the implied social dynamics of a heteronormative relationship. The two protagonists, Genly Ai and Estraven, have an intrinsically platonic relationship, and are unable to bond over an assumed “male” or “female” role within their society. These characters were not raised with an internalised perspective of us and them, female and male: rather, they’re both undeniably equals.

The sexless dynamic between the two characters is currently possible only within the confines of SF. In a world where even today the concept of non-binary and transgender individuals is baffling to many, to be creating a genderless world as early as she did, Le Guin is certainly one of the strongest pioneers for the deconstruction of the modern gender binary.

In another twist of today’s society, Nontraditional Love by Rafael Grugman (2008) puts together an upside-down society where heterosexuality is outlawed, and homosexuality is the norm. A ‘traditional’ family unit consists of two dads with a surrogate mother. Alternatively, two mothers, one of whom bares a child. In a nod to the always-progressive Netherlands, this country is the only country progressive enough to allow opposite sex marriage. This is perhaps the most obvious example of cognitive estrangement. It puts the reader in the shoes of the oppressed by modelling an entire world of opposites around a fairly “normal” everyday heterosexual protagonist. A heterosexual reader would not only be able to identify with the main character, but be immersed in a world as oppressive and bigoted as the real world has been for homosexuals and the queer community throughout history.

Purely queer universes are not seen in mainstream film and television often, if ever. In this respect, the medium may not inspire a complete re-think of life as the audience knows it, but it does stand as a pervasive medium that is able to shape modern generations. In the wise words of Marie Wilson: “You can’t be what you can’t see.” Films and television shows allow the audience to actually see a tangible example of characters interacting with the world, and there is a lot of content in a series that runs for several seasons. Generations of role models can be made, and minds can be shaped to view these characters as familiar and relatable.

The suspension of disbelief required to be immersed in the plot of any SF story gives opportunity for queer characters to exist without introduction, justification or explanation. Xena: Warrior Princess (1995–2001) features a heavily implied romantic relationship between the two main female characters Xena and her sidekick Gabrielle. In interviews, the writers admit that sneaking lesbian subtext into the show had almost become a game. However, other characters never acknowledged the relationship, or gave it a sideways glance. The candid portrayal of such a relationship had a huge impact on the lesbian community in the 90s. Mainstream SF was starting to push the boundaries on what was taboo for global audiences, and it was being very much accepted in the process.

Xena: Warrior Princess, Season 6, Episode 22: Xena and Gabrielle share a kiss in the final ever episode of the series.

In the fourth season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997–2003), a young witch, Willow, falls in love with another witch, Tara. Their relationship is briefly noted by a few other characters, but their lives are soon straight back to slaying vampires, saving the world from evil, and attending school with no negative attention from their peers. Willow and Tara’s relationship throughout the series is raw and powerful, and given the respect and screen-time that any heterosexual relationship would have. If “you can’t be what you can’t see,” then SF in the 90s certainly helped a generation to be what they were seeing: an entire cast of characters who are tolerant towards other sexualities, and confident in their own.

With such examples of female sexuality on screen, it’s hard not to notice the lack of diversity in male and other sexualities. Homosexual males are most commonly portrayed as stereotypically flamboyant, are often persecuted for being so (Lafayette in True Blood, Felix in Orphan Black). However, SF did squeeze out a winner in terms of male sexuality representation in the 2000s. Doctor Who featured the character Captain Jack Harkness in the 2005 series return. He is an openly-pansexual time traveller who journeys with the Ninth Doctor during the 2005 series. So popular that he gained his own extraterrestrial spinoff series, Torchwood, his notorious on-screen kiss with the man whose identity he stole (the real Jack Harkness) was essentially the characters’ “coming out”. The romance lasted one episode, and was taken with no surprise by the other characters in the show. In fact, Harkness is known to be quite the ladies’ man (or man’s man, or… alien’s man, depending on the day), with reactions from other characters remaining consistent regardless of his preference.

Torchwood, Season 1, Episode 12: The popularity of Captain Jack Harkness saw him playing the main character of the Doctor Who spinoff series. SF finally had a queer male protagonist ‘being it’ so everyone could ‘see it’.

SF in the early 2000s can’t be properly concluded without mentioning the cult classic Firefly (2002–2003), in which Inara graced TV sets, radiating the most casual sexual charisma and charm. Within a show based 500 years in the future, Inara is a well-respected, pansexual, high-society courtesan, often considered the most respectable member of the crew of space outlaws. In one episode she takes a Senator on board the ship as a client, who is revealed to be a woman at the end of the episode. The crew is mildly caught off guard, but Inara has a chuckle to herself at their assumption of her heterosexuality.

Both written and on screen, SF has allowed diverse sexualities to be portrayed with an enviable nonchalance that queer communities could only dream existed for themselves in the real world. Mainstream SF films and TV shows, which are not at all aimed at a queer audience, have hosted a wide array of sexualities in the past few decades, playing an important role in normalising alternative sexualities. However, now that the glorious 2000s have passed, SF may not need to pave the way any more. Mainstream comedies and dramas such as Transparent and Faking It are helping to normalise queer culture, as they are centered around queer characters and issues. As well as that, queer characters in other genres are now also operating in worlds where their sexuality doesn’t completely define them (see: Orange is the New Black, Broad City, American Horror Story and Person of Interest).

Queer representation is still far from optimal in any genre. But it seems the real world may finally be close enough to accepting queer culture to casually embrace the spectrum of gender and sexuality. Nowadays, there does not seem to be as big a need for the fantasy worlds of SF to ease audiences into the concept of diverse sexualities on screen. One can only hope this progression moves from imagined realities into modern society, giving upcoming generations even stronger LGBTI role models to not just accept, but to identify with.

Edited by Sara Nyhuis and Jessica Herrington, and sponsored by Shanna Hollich