Our appetite for fish is greater than ever. To tackle the issue of sustainability, we need sound science.

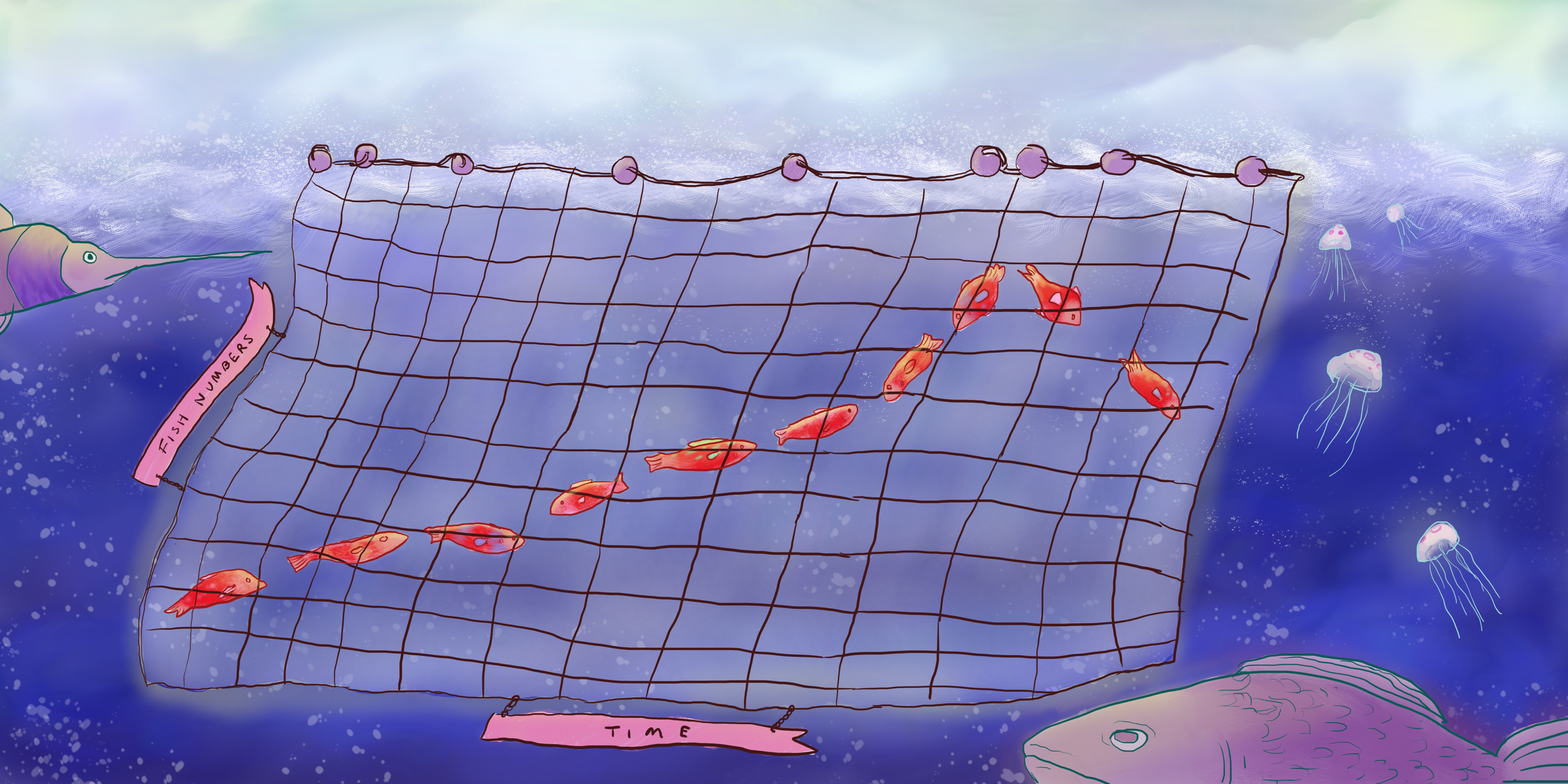

Illustration by Anna Wang

As I helped haul 40 tonnes of fish out of the cold, seemingly lifeless, waters of the Southern Ocean, I struggled to accept that the fishery was being managed sustainably. Within 24 hours, the catch would be processed, packaged, frozen and stacked away — just in time for the exercise to be repeated. A practice being perpetually carried out by a fleet of fishing vessels working around the clock, day in day out.

The productivity of the earth’s oceans is unfathomable. Until very recently the sheer abundance of fish in the sea had led to a belief that the resource was, in effect, inexhaustible. Despite millennia of fishing, humanity had barely skimmed the surface of the ocean’s bounty. Yet within only a generation or two of industrial-scale commercial fishing, this illusion of preternatural wealth had been well and truly shattered.

It can be easy to forget that our dependence upon the sea is largely dependent on wild species and functioning natural ecosystems. Oceans are not farms, they are jungles and should be managed accordingly. If the immense wealth of our oceans is to be sustained for future generations, society must address past and present failures in resource management and environmental stewardship.

Teach a man to fish

Over the past 70 years, the human population has tripled, from 2.5 billion to 7.5 billion, and so has our appetite for fish. Fish consumption per capita has risen from 6.5kg to more than 20kg. Fish is currently a significant source of animal protein and micronutrients for well over half the world’s population. Yet this has come at a cost.

The second half of the twentieth century saw the annual global fish harvest rise from less than 20m tonnes to more than 90m tonnes. This wild harvest has subsequently remained relatively static, despite steady increases in fishing effort, indicative of overfishing and continued expansion of the industrial fishing fleet. The number of fish stocks considered to be overfished has increased from 10% in 1975 to approximately one-third of stocks today, and less than 10% of fish stocks are now considered “underfished”.

Over the past three decades, as the wild harvest peaked, and plateaued, global aquaculture production increased dramatically, from just under 10 million tonnes to just over 80 million tonnes. While potentially relieving economic pressures driving fishing activity, aquaculture can prove highly detrimental to natural ecosystems — particularly in coastal regions, where most aquaculture operations are situated.

Industrial-scale fishing helps feed the world’s growing population, but at what environmental and ecological cost. Jabbi/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Do these statistics foreshadow an inevitable decline into environmental and ecological ruin? While they may appear as yet another reason for pessimism, history and science offers some perspective and allows room for optimism.

How much is too much

Although any good fisheries management framework should prioritise sustainability, the exact definition of ‘sustainability’ is open to interpretation, both in principle and in practice.

Biological sustainability focuses on the preservation of individual species (or fish stocks) over the long-term, and is central to most fisheries’ management frameworks.

In fisheries science, virgin biomass is the estimated size of a population prior to being fished. To get an indication of fishery health, scientists use the virgin biomass as a yardstick to measure existing biomass against.

Because population growth rates (encompassing reproduction, survival, and individual growth) decline when there are too many or too few fish, the maximum population growth occurs at about half the carrying capacity. This is of great importance in fisheries management as it corresponds with the largest amount of fish that can be harvested from a stock on an ongoing basis, or the maximum sustainable yield.

Species with high growth rates like hoki can sustain bigger harvests and are more resilient to overfishing, whereas the opposite is true of species with low growth rates, like the orange roughy. In order to account for some of this variation, stocks are typically managed in relation to the biomass of a population’s breeding individuals — known as spawning stock biomass.

Harvesting at the maximum sustainable yield is inherently risky due to technical challenges, inaccurate or inadequate information, and natural variation. If a harvest exceeds the maximum sustainable yield, then subsequent catches must be reduced in order to avoid a positive feedback loop depleting the stock.

Orange roughy are regularly caught by trawlers, but because they grow so slowly, they are very vulnerable to overfishing. CSIRO/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

The use of maximum sustainable yield as a limit rather than a target would therefore seem prudent. Such an approach also makes economic sense. While fishing at maximum sustainable yield allows for the largest harvest, it doesn’t take cost into account. Put simply, the more fish there are in the sea, the easier they are to catch. Costs increase as populations decrease because it takes more time and effort to catch the fish. So it makes economic sense to fish at a level where the difference between revenue and cost (time and effort) is greatest. This point is known as the maximum economic yield and fishing at this level typically means fewer fish are harvested than at the maximum sustainable yield.

These principles are simplistic but are far from failsafe. Single-species fisheries management frameworks often fail to address important ecological factors such as bycatch, habitat destruction, ecosystem function and how a species fits into the marine food chain. Nevertheless, single-species systems can provide a basis for the development of sustainable fisheries and can also be integrated into multi-species or ecosystem based fisheries management framework.

Fisheries science, if well supported, can provide the frameworks necessary for effective fisheries management across whole marine ecosystems. But the challenge of achieving sustainable fisheries at a global level remains daunting.

An all too common tragedy

The tragedy of the commons describes any situation in which the total value of a shared renewable natural resource is reduced by the collective actions of individuals acting in accordance with their own self-interest. In the ocean, the tragedy of the commons can occur at many levels, between competing nations, companies, or fishing vessels. It has undoubtedly contributed to the destruction of fish stocks around the world.

Traditional ways to mitigate the tragedy of the commons are either absent or highly problematic in most fisheries. Fisheries lack clearly defined boundaries and the threat of stock depletion can be difficult to perceive, especially across generations. Substitutes are often plentiful, either in the form of other fish species or terrestrial alternatives. Community presence is generally limited to those directly involved with the fisheries. Consequently, the implementation of effective community-based rules and deterrents is difficult. This is especially true at scale as the exploitation of resources by non-locals renders most social solutions redundant.

Historically, the development of fishing technology has typically been detrimental to fisheries health. Yet this looks set to change with a wave of new and existing technologies being developed to improve fisheries management. Vessel Monitoring Systems tracking fishing activity; smartphones recording catch data; block chain ensuring supply chain integrity; marking fishing gear with radio-frequency identification; smart scales weighing, measuring, recording and barcoding fish; on-board camera systems observing fishing practices; Artificial Intelligence (AI) measuring discards; innovative new fishing gear improving catch quality; and let’s not forget the drones! These are just a few examples of the many technologies being explored with the goal of improving fisheries management.

Although social cohesion and cooperation were not found in abundance on the high seas or between competing nations in the 20th century, multilateralism and the use of modern technology may allow for many of these barriers to be overcome in the 21st century.

Not so EEZ

Addressing the commons dilemma in fisheries at an international level was highly problematic prior to the adoption of the 200 nautical mile (370km) exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provided nations with a right of first access to resources within their respective EEZs. Before 1982, territorial disputes occasionally resulted in conflict between nations, such as the Cod Wars — a series of militarised interstate disputes between the United Kingdom and Iceland over access to cod stocks in the North Atlantic ocean.

Exclusive economic zones allow countries the first right of access to whatever is within in 200 nautical miles (370km) of their coastlines. Maximilian Dörrbecker/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.5)

As the vast majority of fish populate waters along the coast, or above the continental shelf, the EEZ framework placed most fish stocks (except highly migratory species such as tuna) under the control of individual nations. Over 90% of the global wild fish harvest occurs within EEZs, with the remainder being caught on the high seas. Along with research indicating that over half of all high seas fishing grounds would be unprofitable in the absence of government subsidies, the case for protecting the high seas from exploitation is strong and may soon be a reality.

On the ownership of species

Multilateral agreements brought about the closure of the commons at an international level but they did little to avert tragedy within the EEZs of nations. Successful attempts to close these commons have typically involved moves towards the privatisation of fisheries. The process of privatisation involves the conversion of resources from public goods into private property; thus limiting access to the resource and reducing competition.

A favoured means of achieving fisheries privatisation has been the creation of Individual Transferable Quotas, which are essentially tradable shares in a fish stock. Individual transferable quota owners are entitled to harvest a percentage (proportional to their holding) of an annual catch. The body responsible for managing the resource determines and allocates this annual catch, which may fluctuate in relation to the health of the fishery. Stewardship of the asset is therefore encouraged as the value of quota is largely determined by the health of the fishery.

Despite proving successful in addressing the commons dilemma, the privatisation of renewable natural resources is economically flawed. This is because maximising the regular income from a resource (known as economic rent) is not the same as maximising the value of a resource. In circumstances where excess returns from overfishing could be invested elsewhere and generate greater profits than would be obtained by sustainable harvest, it can be more profitable to harvest a fishery unsustainably. Privatisation, therefore, cannot be relied upon to address overfishing in and of itself — regulation is necessary in order to achieve sustainable fisheries.

The Cod Wars erupted in between Iceland and the UK over fishing rights in the Arctic. Magnus Manske/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-2.0)

In 1986, New Zealand became the first nation to embrace the privatisation of fishing rights. The New Zealand Quota Management System. largely closed the commons and facilitated effective responses to overfishing. However, the system is far from perfect and has been criticised in relation to labour issues, unreported catch, fish dumping, lack of research funding and poor governance. These issues are contentious, which is understandable given the stakes.

In cod we trust

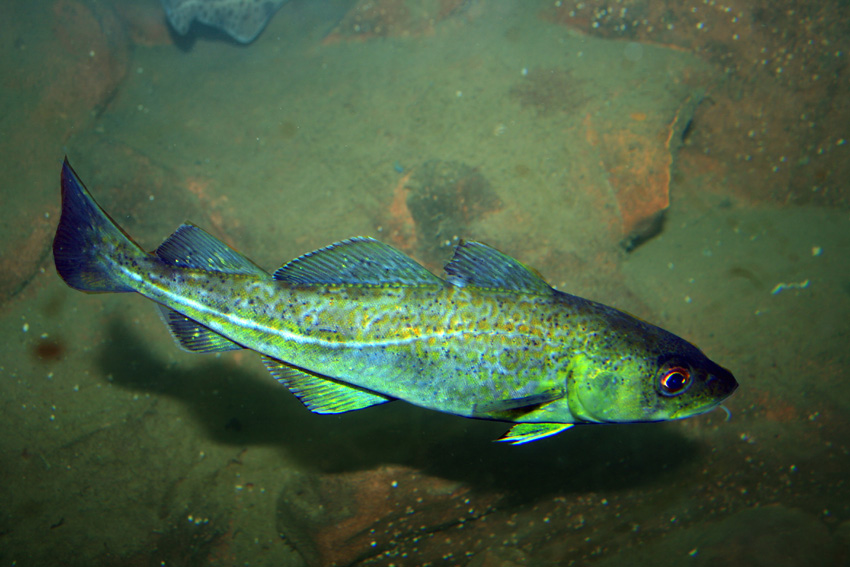

There may be no greater motivation to manage our fisheries sustainably than the tale of the Northwest Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua). Located off the banks of Newfoundland, the Atlantic cod fishery was first fished by the indigenous Beothuk, then Vikings, then fishermen from Western Europe. Around the turn of the 17th century, English fishing captains are said to have reported cod shoals "so thick by the shore that we hardly have been able to row a boat through them".

Having sustained centuries of increasingly large harvests, the arrival of an international fleet of industrial factory trawlers during the second half of the 20th century led to extensive overfishing and the collapse of the Northwest Atlantic Cod stocks. The fishery wasn’t closed until 1992, despite the annual catch having peaked 24 years prior in 1968. Technological progress, ecological ignorance, bad science, cultural and social dependence, and gross mismanagement were all culprits in this catastrophic failure. After 25 years of ‘rebuilding’, Atlantic cod stocks remain precariously placed.

Coming to terms with the state of global fisheries can be challenging in many respects: scientifically, historically, socially, and emotionally. To top it all off, the effects of climate change mean that fisheries management won’t get any easier.

Global progress towards sustainable fisheries has been inadequate. Strong divisions exist on the issue across society, within academia and even between environmental organisations. Yet strong management, informed by well-resourced science, can deliver sustainable fisheries. What appears to be missing is the social cohesion required to facilitate meaningful change.

Edited by Sumudu Narayana and Ellen Rykers