Human-like aliens have been a staple of sci-fi cinema for over a century. Are modern films breaking the stereotype, and could they prepare us for a real-life first encounter?

Illustration by Tegan Iversen

Spoiler Warning: General themes and plot points of the film Arrival (2016) are discussed in this article.

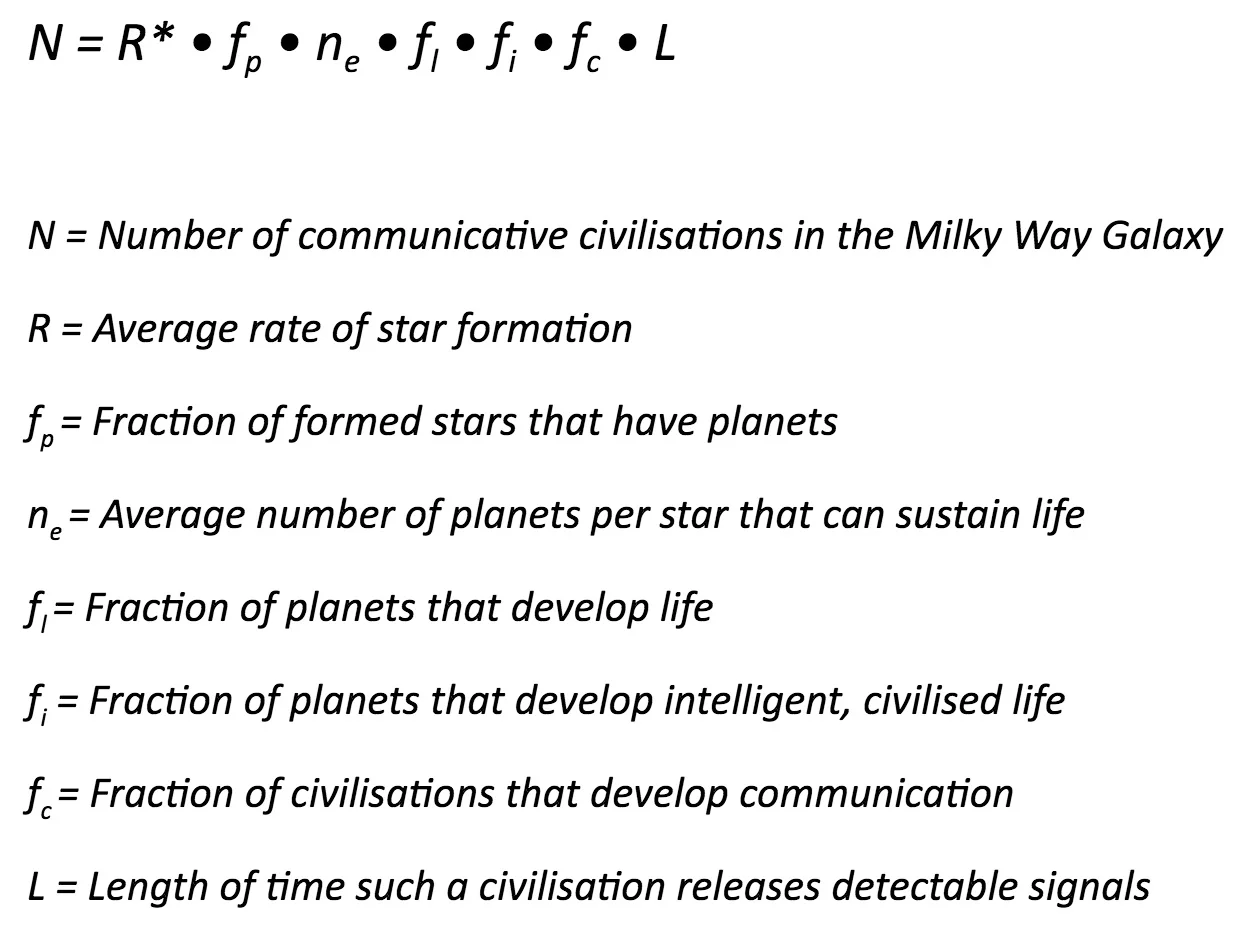

Have you ever wondered if humanity is alone in the universe? Have you thought about alien life, and where it might be hiding? Or how many other life forms there are? Luckily, there’s an equation for it. Drake’s equation is a mathematical formula to estimate the number of intelligent alien lifeforms within our galaxy:

Not a single value of the above equation is 0 (because there’s us!). This means there may be a chance of life on other planets: if not in our galaxy, then almost definitely in the wider universe.

Even before the Drake equation, humanity has had an obsession with alien life. What other creatures could be out there among the countless stars and planets beyond our reach? We have long imagined what creatures from other planets could look like. But if we were to make contact with an alien race tomorrow, would we be prepared? In a time when science is breaking barriers on our quest for alien life, our filmic representation of humanity’s relationship with alien life is still following the same old tropes, and has for decades. Is this narrowing expectations about what life in the universe has to offer, or can science fiction actually help broaden our collective mind?

Since the early 20th century, film has dominated visual media for fiction and non-fiction alike, and the growth and evolution of aliens in cinema is nothing short of astounding. However, these depictions of life beyond our world often follow a very strict archetype, and very few films manage to reach beyond the idea of a humanoid alien with four appendages and a head. While some may venture out into tail territory, there seems to be an integrated acceptance that the human physique is the most evolved, that somehow this fleshy prison with relatively brittle joints and low mobility is the best possible design for highly advanced lifeforms. In reality, evolution on other planets is incredibly unlikely to result in anything resembling our human form, but the nature of humanity is that we have difficulty perceiving anything too different from ourselves.

Humanoid aliens, as seen in War of the World (1953), were the most common form of aliens in film for decades.

One could delve deeply into the psyche of humanity, and call on our arrogance at presuming ourselves to be the most advanced, or being unable to look beyond ourselves. Surely there is a lot to explore there, but I take a more practical approach.

Today, we can digitally create anything our imaginations dream up, in any scenario we choose — so why are we still seeing the same three archetypes over and over again, with the same social commentary played out on repeat? For this, we can thank our humble beginnings: Aliens look like humans because humans create aliens.

When humanoid aliens first appeared in films, there was little freedom in special effects. Directors were more inclined to dress an actor up in a costume rather than create a completely original and biologically unique alien that they had to figure out how to portray on screen. This means that four appendages and a head was the go-to.

In 1902 one of the most influential pieces of cinema was created: The French silent film Trip to the Moon. With a running time of 14 minutes, it doubled the usual five to eight minute running time of films of that era. Director Georges Méliès featured a range of innovative cinema techniques, including wipes, fades and primitive special effects. Among all these industry-changing elements, Trip to the Moon included a run-in with lunar inhabitants. These were simply stage actors dressed in body paint, odd clothing and funny hats, but they were the first onscreen science fiction depiction of life beyond Earth, and the one we so resolutely stuck to. Over the next five decades there were only a handful of science fiction efforts, including Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924) and Flash Gordon, but none were ground-breaking in their depictions of alien lifeforms.

Instead, creators used the genre as a metaphor for political and social events of this time, able to mirror our own world with an imagined one. Aelita: Queen of Mars is commonly viewed as a thinly veiled propaganda film for Bolshevik Russia, depicting the destruction of the capitalist inhabitants of Mars. Flash Gordon, on the other hand, played into the ‘America saves the world’ trope, which is still running rampant to this day. In the earlier science fiction films, it wasn’t about what we do when aliens arrive, how we go about finding them, or pushing the boundaries of biology — it was about using otherworldly societies as metaphors for current world issues, be it communism, fascism or war.

Real interest in extraterrestrial life boomed in the 1950s after two high profile UFO sightings, and science fiction became a hot commodity. Two of the earliest films depicting humanity and alien life were The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), and The Thing From Another World (1951), presenting highly contrasting views. In the early 1950s, the world was living in fear of nuclear war and interest in science grew rapidly; the Cold War was escalating, and communist paranoia was rife throughout the United States. These factors combined saw science fiction fully realised as a medium for social commentary. The Day the Earth Stood Still gave us a peaceful alien race warning humanity of the dangers of nuclear war, whereas The Thing From Another World took a more militaristic approach, urging us to watch the skies. The relationship between humanity and alien life, unfortunately, hasn’t seemed to break out of these barriers ever since their creation. Science fiction’s role as social critique, at least when it comes to alien films, has become stagnant.

In 1951, The Day the Earth Stood Still warned us to “Watch the skies”.

Being able to perceive frame-depth with the development of 3D cinema inspired new and wondrous alien lifeforms, while creativity in how we interacted with them came to a standstill. The use of puppetry was common from the 1950s, however the image of two arm appendages and a head with two eyes continued to pervade alien creation. It was simple, effective and familiar. Sheryl Vint, author of Animal Alterity, says that the familiarity, and therefore relatability, is key to the success of science fiction, and is what makes it both relatable and othering for the audience.

In 1957, Not of This Earth delivered two prevailing alien archetypes: the potential threat of alien life, and face-hugging, insectoid aliens. This independently made, low-budget film broke the alien stereotype (and gave us a new one) by bringing an entirely new and original vision for the evolution of life beyond our planet. It was simply a painted crab carcass on top of a broken umbrella, yet this flying, face-hugging alien went beyond anything previously attempted in early science-fiction. We saw another brand new alien in The Blob (1958), but this ‘ooze’ creature became inspiration for countless reproductions and simply became another alien archetype. Creators seemed content to stick with these imaginary forms for many years, even while prosthetics and practical effects became more intricate, and actors were able to better hide their form.

In 1979, Alien blew audiences away with a fully explored alien lifecycle. A totally reimagined three-stage development with embryo-injection, parasitic larvae and a fully-formed predatory adult brought new elements of science into the genre. These artistic creations were also the pioneers of true alien horror films, where monsters thirsted for human blood and Earth became the world for invading alien races to conquer. The insectoid alien image hit popularity in 1997 with the release of Starship Troopers. Originally intended as a satirical commentary on war and American society, the terrifying visage and unity of these ‘hive mind’ insectoid aliens birthed a third alien archetype that is still going strong today.

Alien (1979) is renowned as a classic science fiction film, and a pioneer of the sci-fi horror genre.

From then until now, we have seen special effects and CGI continue to advance. Actors climbed out of their body suits and began to be replaced by computer-generated characters, but science fiction films still follow the same path. Aliens remain familiar and terrifying, and seem hell bent on threatening human existence. The few that depict peaceful interactions, such as E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, all feature aliens of the humanoid variety (and one cat).

Why is this? Why are there no alien drama films with physiologies completely different from our own? Can we imagine a peaceful interaction with an alien race we share no similarities with, or is the human condition one where we immediately label anything we do not understand as a threat?

The idea that different equals danger is not new for humanity, and is something we still struggle with as evidenced by the inequality, discrimination and wars that have persisted throughout history. Current technology in cinema has advanced so far that we can create mythical creatures from scratch and animate their performance to match the actor. We can even create an on-screen biological entity that has never been imagined before.

Benedict Cumberbatch as Smaug in The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug. Motion capture and CGI technology enabled the terrifying dragon to be acted out by Cumberbatch, and mapped to his movements.

Our imagination is the limit: If you can think it, you can build it. But our mentality may be so ingrained that we cannot fathom a scenario where we as humanity boldly step forward to embrace and learn about an alien race we cannot relate to in any way. Or perhaps it is simply an artistic choice by filmmakers, to avoid difficult questions and logical leaps, to escape plot-hole arguments, and avoid involving too many scientists to maintain accuracy. If an alien race cannot hear, see or gesture, how would they communicate? The idea of alien species that share no common senses, and the challenge of discovering how to communicate with them, might have been put in the too-hard basket.

Expanding our human-centric perspective for a moment, imagine aliens that communicated with each other purely via the release of specific pheromones. No eyes, no ears, no need for limbs in regards to communication; purely pheromone receptors and emitters. Imagine initial interactions between humans and these beings, with no discernible communication methods. How would these aliens make their peaceful intent clear? Would humanity have the patience and the drive to create a method of communication, or would silence be taken as a sign of hostility?

In 2016, we had the first non-hostile, non-humanoid alien contact film of this century. Director Denis Villeneuve stepped up where many other filmmakers have not, tackling many of these questions with the most current example of alien ingenuity. Arrival features aliens that shatter our three prevailing archetypes: they are not even close to humanoid, with seven appendages and no focal point such as an eye or a head. It also explores humanity’s difficulties when faced with the realisation that not only are we not alone in the universe, but we are incredibly outmatched technologically. A technologically superior race is a common depiction in alien films, however, Villeneuve takes it two steps further: Peaceful aliens on a diplomatic mission, with no common way to communicate. The film utilises the science of linguistics to create a method of communication between the visiting aliens and the team assigned to work out why they’re here. It explores the idea of humanity’s response to impending silence, and is a blatant call out to our world to learn to work together and cooperate, because as the arriving aliens say, we need to.

With this standout example of a peaceful, science-based, military-slamming alien film, could we be seeing the dawn of a new age? One where science fiction breaks away from the familiar, and utilises the genre’s freedom to return to investigate the true expanse of possibilities for life outside our solar system? An age where we step away from the tropes and truly embrace the science that is so very important in science fiction, and use its ability as social commentary to encourage our world to be peaceful, not hostile?

Well, to be blunt: probably not.

Arrival may have casually shattered several prevailing alien tropes while simultaneously showing us that communication is paramount over warfare, but the practical, real-world side of extraterrestrial contact is significantly less advanced than our fantasies. SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Life, based in California) have published a post-detection policy as guidelines for those that discover any alien signal, but government agencies have had no input towards similar protocols. The closest thing our planet has to an alien intermediary is NASA employee Catharine Conley, whose job title is Planetary Protections Officer. It is her responsibility to contain and safeguard all interplanetary samples and collections. Conley is Earth’s one and only interplanetary protector.

Catharine Conley is a Planetary Protections Officer employed by NASA. She is the closest Earth has to an alien intermediary. NASA (public domain)

Evidently, preparation and planning for any possible alien contact is low on the list of priorities for leaders concerned with their own nations. Governments are in agreement that extraterrestrial contact is unlikely to happen any time soon, but as science progresses and we are capable of moving further and further out of our solar system, the reality that we can’t possibly be alone is imminent. One day, contact films may no longer be products of our imaginations.

Luckily, six separate professional space societies have put together and endorsed nine protocols detailing what to do in the event of extraterrestrial contact. While there is no steadfast law about how to act in the event of an alien detection, keeping to these accords reflects the openness and collaboration so greatly valued among our scientific community.

It has taken over a century of extra-terrestrial movies for filmmakers to create a scenario of first alien contact without invasion, without hostility, and without a humanoid alien race. It has taken just as long to bring science to the forefront of science fiction, embracing humanity’s ability to innovate and communicate while still surprising us with the otherworldly and strange. Arrival is only the most recent in a long line of alien movies, many filled with tropes and expectations that humanity may associate with our galactic neighbours. Should we make contact with aliens tomorrow, we can only hope that people’s minds do not stray to The War of the Worlds (1953), where aliens are here for our resources, or to The Host (2013), where they are here for our bodies. Hopefully, the alien probe trope is far from our thoughts and we refrain from assuming they will shoot first like they did in Independence Day (1996).

Films are much more than entertainment, they provide us with a lens through which to view the world. These representations of alien life seem harmless now, but if we meet the real thing, films like Arrival could provide a very real example of how to understand a new species, rather than shoot first and ask questions later. When faced with the realisation we are not alone in the universe, one thing becomes very clear: No matter which country you live in, to the rest of the universe, we are all Earthlings.

Edited by Sara Nyhuis and Cherese Sonkkila