Scientists need to craft a logical narrative out of their data, even when the literature looks more like a Choose Your Own Adventure.

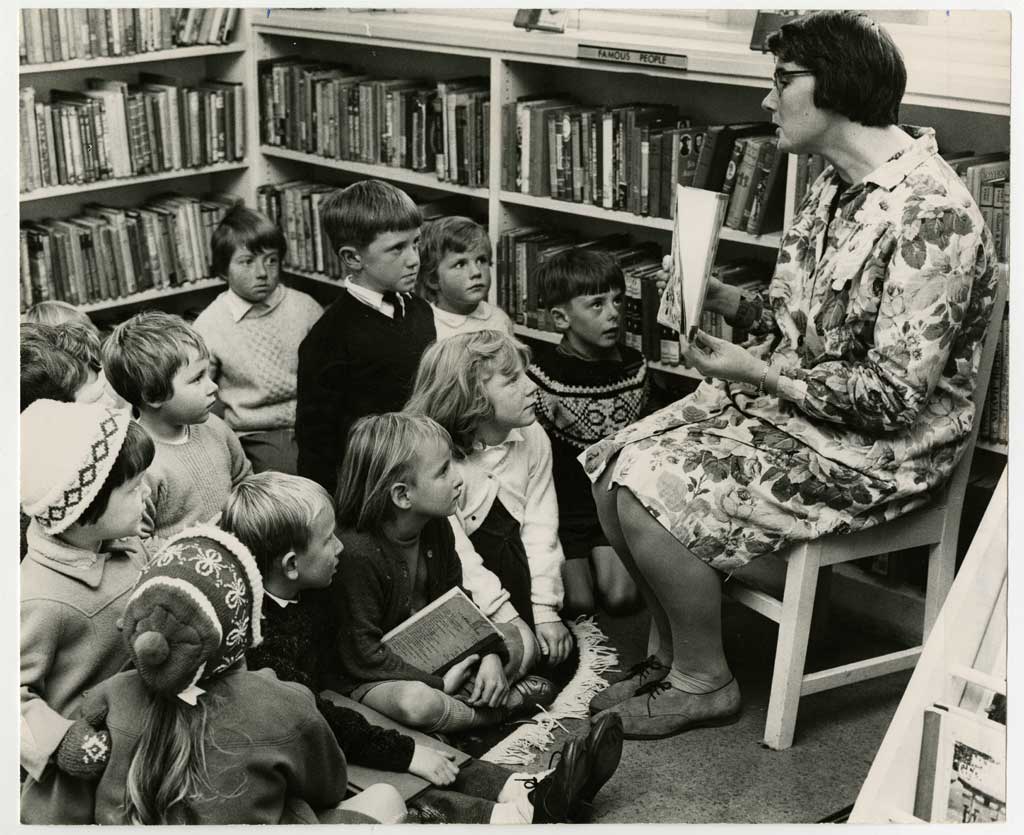

Crafting your research into a narrative is incredibly important for scientists. Christchurch City Libraries/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Overt Analyser is a monthly column by Chloe Warren that reflects on her experiences as a twenty-something scientist. Chloe is a PhD student in medical genetics at the University of Newcastle and really thinks too much about most things.

As I sit in our research team’s regular drug trial meeting, suggesting how we can gather data, which analytical methods we could use and potential contacts in the field, I internally blush. Who am I to make these suggestions? Silently contemplating with these newfound self-assurances of competence, I slowly realise: I am qualified to be here.

Each time someone asks for my advice or I’m sought out for my skills, it surprises me. It surprises me that other professionals are taking me seriously, because I have always just assumed that I’m a second-rate scientist. There are some things about my field that I just don’t get. I’m not talking about certain disciplines or methods – we can never know everything. I’m talking about a skill that lies at the very heart of the scientific discipline. I’m talking about storytelling.

Don’t worry, I’m not suggesting that scientists are fantasy writers. But we are writers nonetheless. Each day, scientists carry out experiments that generate data. Eventually, they’ll have enough data on their plate to tie together into a scientific publication. They’ll write down everything they did and give it a beginning, a middle and an end. In short, they will craft a narrative. In an attempt to understand your shiny new data, you must understand its context. Therefore, this narrative is heavily dependent on what we already know.

Science can really mess with your sense of self. Brandi Eszlinger/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Unfortunately, in my field of molecular biology, what we already know is constantly being ripped apart and re-modelled by some, and sternly defended by others. It’s the nature of the beast. As well as there being conflicting information, there can also just be an overwhelming amount of it. A literature search for my particular protein family of interest generates over 50,000 scientific publications. Let’s call it 50,000 and ignore that fact that there are approximately 35 new papers published per month on this topic. Say I decided to read all of these papers, designating one and a half hours to each one, and spent seven hours a day, seven days a week dedicated to this humble new hobby. Twenty-nine years later I’d be just about finishing up. How’s that for a realistic deadline?

When people publish in my field, I assume that there’s some skill they have that I don’t. I tried to write a literature review (a scientific publication summarising the current findings of a particular area of research) a year ago, and it was almost impossible. I worried that my struggles had me marked forever as a bad scientist.

Thanks to the good graces of my friends and family, the support of my colleagues and mentors, as well as a series of fortunate events, I’m now in a different place. I’m in a place where I can see that my capacity to doubt my ability to ‘story tell’ is not some shortcoming of my skill set or personality. As put by Yuri Lazebnik in his famous 2002 essay, Can a Biologist Fix a Radio, “humans can only keep track of so many variables”. Information overload is an experience that must be shared by many other scientists, who either deal with it by simply overlooking their doubts, or by shouting loudly over the top of them while plugging their fingers in their ears. That one requires a strong sense of personal confidence – or arrogance, depending on how you look at things.

It’s at this point that I stop to address the hoard of bioinformaticians who likely have a lot to say on this matter. Bioinformaticians use a variety of techniques from computer science, mathematics, statistics and engineering to analyse the masses of data produced by modern biotechnology methods. Fluency in some field of bioinformatics is fast becoming an integral part of any life scientist’s skill set. We are all becoming part-time bioinformaticians. However, no matter how fluent scientists are in this increasingly vital language, there’s a difference between analysing a large data set and interpreting its significance in the wider field. Again, we become limited by the human brain.

As science digs down into the details of reality, there will always be more to discover. So don't worry if you don't know everything. Morten Skogley/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Of course, the capacity to tell a story about one’s research is important not just for getting it on paper in a coherent format, but also for making it communicable and marketable to a wider audience. The best science communicators are those who are able to break down a chaotic mess of complicated scientific theories, methods or processes into a series of digestible, relatable and interesting chunks. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, then please flick through the archives of Lateral, or treat your ears to a couple of RadioLab episodes (this one is my favourite.) Science needs to be able to be communicated, or there really isn’t much point in doing it at all. Also, if you can’t communicate your science, you can’t sell your science, which means you will never get funded for your science, which means you probably won’t be able to do any more science — and now you’re fired, sorry.

So we know that successful scientists need to be great at crafting a narrative. But it unnerves me that for every researcher who reads a batch of papers to explore the context of their work, there is another researcher in some Sliding Doors-esque multiverse who will read a different batch of papers; although both Gwyneth Paltrows entered this paradigm with the same dataset, each will leave with a different interpretation. That’s what made review writing so difficult for me – part of me felt like I couldn’t start writing until I knew the entire field. What if some accused me of getting my facts mixed up because I had come to a conclusion about something after reading papers X, Y and Z, as opposed to X, Y, and Q?

Limitation of human knowledge is always going to exist, in the same way that science will never be ‘finished’. That’s why rigorous (sometimes downright intimidating) debate is an integral part of academic culture. That’s why it’s called “science” and not “A List of Facts Upon Which We Have All Agreed”. But when it comes to the day-to-day practice of science and understanding my results, how can I begin to be confident in my work when there is so much information available and there are so many scientific stories out there?

The truth is, none of us should ever be 100% confident in our scientific conclusions. It’s true that rigorous debate is part of the scientific process, but the minute personal confidence enters into the equation, it’s not science being practised, it’s egotism. While you should always be able to confidently argue the validity of your conclusions, you should also be open to other possible conclusions. Actually, good scientists should welcome other interpretations — it means people are interested!

In an ideal world, the human brain would be a limitless data-handling machine. But it’s not. So while we wait for the supercomputers to take over, we’re just going to have to get used to something: namely, if you’re going to make a scientific argument, you’re going to have to start somewhere. You might not feel ready just yet, but I for one don’t want to wait 29 years and also, no one knows how multiverses work. Yet. Relax — every story has to have a beginning.