Cyborgs, the fusion of human and machine, have fascinated us for over a century. Today, contemporary artists are making adaptations to their own bodies and exploring what it means to live as a cyborg.

Illustration by Kayla Oliver

In 1641’s Meditations on First Philosophy, French philosopher René Descartes implored us to "consider the body of a man as being a sort of machine" – a machine "composed of nerves, muscles, veins, blood and skin." While Descartes was simply attempting to explore the nature of the soul, a similar fascination with the body qua machine has popularly persisted within the arts and humanities fields well into the present day, presenting an interesting question: to what extent does art reflect the reality of cyborgism? Do modern cyborgs imitate art? Or are the lines between ‘reality’ and ‘fiction’ not as clear as we would like to think?

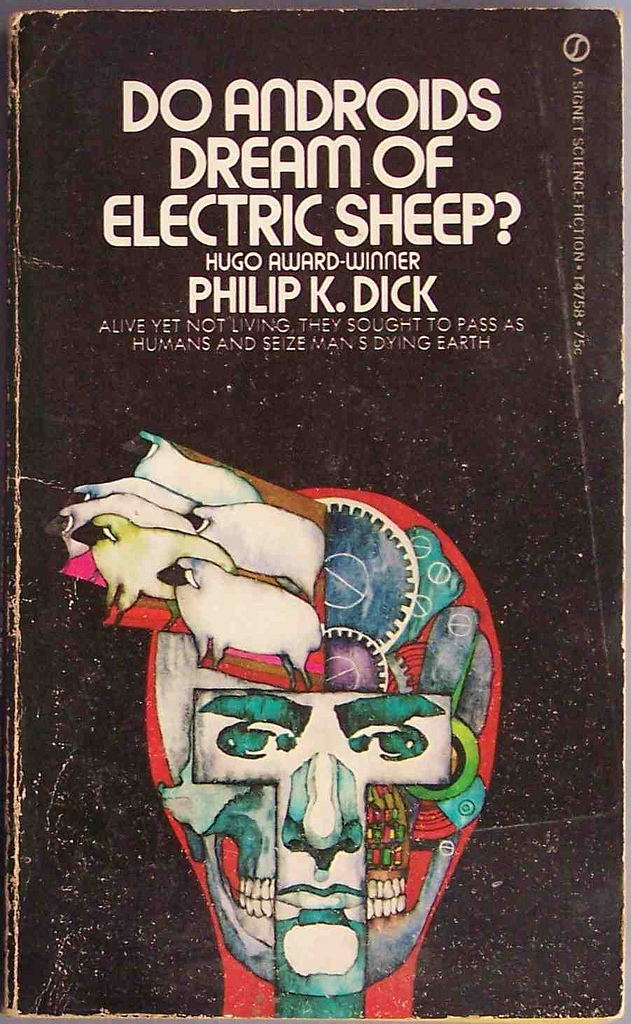

Fast-forward 300 years from Descartes into the 20th century: popular media and the arts become especially interested in cyborgism – an interest that’s continued well into the present day. Hearkening back to Descartes philosophical concerns, stories of science fiction initially exploded with (what can almost be described as) an obsession with artificiality’s hypothetical implications on the nature of ‘humanity’ and personhood: "at what point, if altered, does a person stop being human? And if they were created, were they ever human?" This question probably best exemplified in the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and its 1982 neo-noir film adaption, Blade Runner.

Philip K Dick's seminal short story about humanity and technology was adapted into the neo-noir classic film Bladerunner in 1982. Chris Drumm/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

While these narratives explored the ideas surrounding the imitation of the human form in androidism, it was Steve Austin of the earlier 1970s television series The Six Million Dollar Man, who was rebuilt to be "better, stronger, faster" (and have seriously tacky sound effects). Thus the conception of ‘cyborg’ was cemented into popular consciousness: a biomechatronically enhanced organism. And while the term ‘cyborg’ itself had existed since 1960 (with the show based on the 1972 Martin Caidin novel, aptly titled Cyborg), it was Lee Majors’ depiction of cyborgism that has pervaded popular culture from thereon in.

Since then, ‘Austinesque’ cyborgs have appeared in almost any great science fiction media – from film to video gaming. 1977 saw galactic super-father and notable cyborg Darth Vader gracing our cinema screens in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope – an appearance that, as Austin before him, has permeated popular culture; his infamous quote, "I am your father," has reached almost proverbial status. Ironically, his son, Luke Skywalker, would end up tracing daddy’s footsteps following a fatal filial dispute in 1980’s Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back. Additional (often derivative) Austinesque portrayals of cyborgism have, since then, been borrowed and employed in films to varying degrees of success and failure, with 2001’s Jason X (where an ever-friendly Jason Voorhees goes on a sci-fi slasher rampage on a space-station following a biomechatronic revival) being a notable example of the latter.

No different are video games, which have also wantonly portrayed cyborgs since their inception. The combination of a fulfilment of industrial masculine power fantasies, the influence of science-fiction films and comics of the time, and the media-form’s ability to effectively portray what film was—for a long while—still unable to convincingly do so, saw the pixel and polygonal portrayals of cyborgs explode.

Notable games included 1987’s Bionic Commando for the Nintendo Entertainment System (where the hero Ladd Spencer employs his biomechatronic arm as a grappling hook to cross gaps and climb heights), and the later 1998 PlayStation stealth-action game Metal Gear Solid, where an elusive cyborg-ninja named Gray Fox shadows the game’s protagonist, not clearly quite friend or foe (with this year’s distant sequel, Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, featuring a cyborg protagonist).

A still from the 2011 cyberpunk role-playing game Deus Ex: Human Revolution. Bago Games/Square Enix/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

More recently, Eidos Montreal’s 2011 role-playing game Deus Ex: Human Revolution featured protagonist Adam Jensen, who was rebuilt with futuristic prosthetics following a terrorist attack. The game heavily explored themes relating to cyborgism and the ethics surrounding it. With its sequel, Mankind Divided, scheduled to release in 2016, it’s clear that cyborgism is still of huge interest to video gaming as well as the wider arts.

It would seem that cyborgism, as presented by the popular media, is an enhanced human being capable of inhumane (often physical) feats. But how does the oft-employed Austinesque cliché of the arts compare to cyborgism today?

Simply put, British-born Neil Harbisson can have phone-calls in his head. Not only that, but he can receive images directly to his mind over the Internet — all thanks to an antenna-like implant into his skull which he calls his ‘eyeborg’. Harbisson was born with a rare form of colour blindness called achromatopsia that limited his vision to greyscale. But like the redemptive cyborg stories of TV, film and comics, the antenna (which is osseointegrated to his occipital bone) now allows him to literally hear light frequencies. Just as the fictional Steve Austin’s capacities were rectified and improved in The Six Million Dollar Man, so too were Harbisson’s; he can now perceive colour beyond of what we as humans are biologically capable. Speaking with The Guardian in 2014, Harbisson explained that his eyeborg "detects the light’s hue and converts it into a frequency I can hear as a note".

Neil Harbisson with his ‘eyeborg’ implant. Moon Ribas/Wikipedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Before his modification, Harbisson had studied music and art from a young age. At 16, he studied fine art at Institut Alexandre Satorras, Spain — moving to Ireland at 19 to study piano at Waltons New School of Music. At 20, he traveled to England to study composition at Dartington College of Arts. As an accomplished and (these days, rarely) qualified musician, Harbisson’s ability to hear light frequencies has had a huge effect on him as an artist.

In an interesting intersection of science, fine art and music, Harbisson decided to put his eyeborg skills to an interesting use: the painting of sound, as perceived through his cyborg modifications. In an interview in 2014, Harbisson explained how his new faculties inspire his work: "I painted a speech by Hitler and one by Martin Luther King, translating their sound into colour. Then I asked people to guess which was which. They often got it wrong." Through his employment of his eyeborg in his art, Harbisson has been dubbed a ‘cyborg artist’ – if not the first of his kind. Perhaps most interestingly, Harbisson’s work sees a full circle of the cyborg narrative: from the arts we conceived of cyborgs; in science, we created them; through them, they create art.

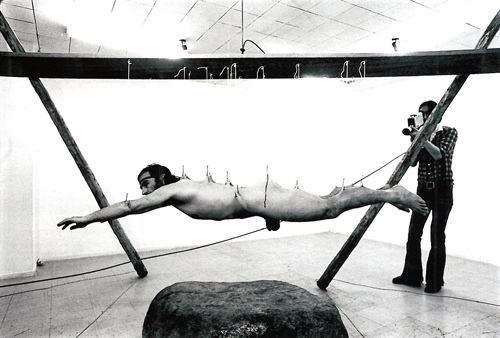

Australia itself has also borne a cyborg artist. The performance artist Stelarc often employs cyborg-like enhancements in his acts. Unlike Harbisson, whose story of cyborgism is restorative, Stelarc’s object of cyborgic self-alterations has been vastly more aesthetical, kinetic and poetical. Stelarc, née Stelios Arcadiou, was born in Cyprus in 1946. After moving to Australia, Stelarc studied Arts and Craft at TSTC, Art and Technology at CAUTECH and MRIT, Melbourne University. He’s perhaps best known for the variety of suspension events where he hangs himself via meathooks attached to his skin — perhaps one of the stranger, yet fascinating, examples of performing arts. He’s performed his body-modifying suspension events over 25 times since the 1970s.

His foray into cyborgism, however, has seen him surgically attach a third hand and, later, an ear to himself — all in the name of artistic expression. Where Harbisson and Stelarc differ is in that, while Harbisson’s cyborg alterations are tools for him to produce art, Stelarc’s cyborgic alterations are the object of the art – they themselves are performed as the goal of the art, rather than the means of producing it. However, both these enhanced men would agree that cyborgism is of paramount import in our increasingly technological societies, with Stelarc going so far as to suggest that we as humans should be the ones adapting to technology; "perhaps an ergonomic approach is no longer meaningful," he opined in a 1995 interview. "We can’t continue designing technology for the body because that technology begins to usurp and outperform the body. Perhaps it’s now time to design the body to match its machines."

Stelarc during one of his suspension performances, ‘Stretched Skin’, Sydney, 1976. Biennale of Sydney/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Harbisson and Stelarc paint an interesting picture of how we should conceive of the modern cyborg – one that’s explicitly linked with the arts. From the ashes of a (now unpopular) tradition in sci-fi, cyborgism has once again returned to its roots: expression. Even in cases of bionic legs being employed to restore bipedality, the nature of cyborgism is inherently kinetic and rooted in performativity: we judge cyborgic enhancements’ successes on their performances – just as in the arts. Compared with the Austinesque portrait of the enhanced pseudo-Nietzchean ‘ubermenschen’, reality’s cyborgs are less ‘super’ than they are simply expressive. The power of cyborgism is in its reparability and capacity for alteration than the 20th century sci-fi prospects of the enhancement — at least ‘enhancement’ as defined by 80s sci-fi action movies.

While Stelarc implores us as humans to adapt ourselves to technology and Harbisson promotes social progress through his ‘Cyborg Foundation,’ their idyllic cyborg utopia seems a far cry from the reality of today. While body modification is becoming increasingly popular (with advents of personalized art such as scarification, magnetic implants and more, becoming more of a norm), popular zeitgeist is still heavily entrenched in a pseudo-Christian ethos that, to one degree or another, sanctifies the body.

Yes: organized religion is becoming increasingly unpopular in our modern Western world. However, the remnants of this morality can be seen across society: from our legal system that presumes innocence, our social welfare systems that protect the ‘blessed meek’, and popular attitudes towards promiscuous sex seen to ‘sully’ our bodies’ dignity. In true Christian fashion (borrowing from the classical thought of Plato), worthwhile pursuits are of the mind, and the lower, more animal (sometimes dubbed ‘sinful’) pursuits are of the body — with recreational cyborgic pursuits of the latter. We only need to look at the swear words we use in everyday language to understand how our society denigrates the body to a status of ‘dirty’; if not sexist, swearwords nearly always relate to parts or functions of the body. (As a fun exercise, try to think of some counter-examples!)

Stelarc and his third ‘ear’. The next stage of his project is to have a microphone inserted and connected to the internet. Anyone with internet access will be able to listen in to the ear, in real time. Andy Miah/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Now this way of thinking is not inherently bad, though it does hamper the aims of people like Harbisson and Stelarc (as well as all those 1980s sci-fi media aficionados) who hope to forward the agenda and progress of cyborgs. Yet society is changing. For a generation raised on slasher films, many barely bat an eyelid at gore, and tattoos and piercings are becoming increasingly common. Perhaps the future Harbisson and Stelarc hope for is still awhile away, but their goal, if arguably not already here in one form, may be but a few logical steps down the line.

While the second half of the 20th century would have us define cyborgism as an enhanced human, and Harbisson and Stelarc present an example of cyborgism that is inherently preformant, kinetic and expressive, we ourselves may already be cyborgic. For what is a cyborg if not an organism that’s physiological capabilities are extended with technology? Surely the modern person’s dependence on smartphones, combined with the Internet, fits such a definition: symbiotically attached in all but name, our mental faculties relating to personal organization, community, communication and knowledge are extended every day. (Thanks, Wikipedia.) Perhaps it’s not a perfect analogy, but with the increasing acceptance of and dependence on budding technology combined with an increasing acceptance of body modification, surely bionic integration of similar technologies are but a stone’s throw away.

Though admittedly, a day where our iPhones are implemented into our arms does make me shudder. And in that way, Harbisson and Stelarc’s fight to increase popular acceptance of such a premise will definitely be met with backlash, but aren’t all the great battles of history? If that fight means a future where I can run to the same sound effects as Steve Austin, they’ve already won me over. In such a world, a literal read of 1641 Descartes may ring truer than ever: "What do I see from the window but hats and coats which may cover automatic machines? Yet I judge these to be men."